When Rebecca Peck Jones died Oct. 22, 2006, at her home in Riverside, Calif., she left us a legacy of art and wisdom. Using the timeless language of clay, ink, and paint, she translated what she saw and sensed in the world and beyond. But she was fluent in words as well, beautifully-and often humorously-voicing her philosophy of art, spirit, and life itself. "Joy, oh bliss," she would sigh, either ironically or jubilantly, at the unfolding of life. "A bad patch," she would say of any personal misfortune.

Becky's essence reaches out to us from her sculptures, drawings, and paintings, particularly those she created of the women, children, and animals of Cairo, Egypt, and Amatenango del Valle, a tile and adobe village in Chiapas, Mexico. Filling sketchbook after sketchbook in Cairo, one concept began to emerge. Becky wrote, "as human beings on this planet, we share many things; a love of beauty, family values, an energetic longing for the 'good life' -in whatever way it might appear as 'our culture' or 'our individual heritage.' " Becky sought to learn, work, and understand "the spiritual side of life and mud" and to translate these ideas into clay. "I base everything on spiritual development," she said. "I think the bottom line is your own spiritual evolution and how you relate to something that centers your life and is meaningful." Becky was a lifelong Christian Scientist and was influenced by the writings of Mary Baker Eddy, Albert Einstein, Henry David Thoreau and Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky. In a 1993 brochure for a Riverside Art Museum show, she wrote:

In the same Riverside Art Museum show brochure, she speaks eloquently of her medium:

In recent months, Becky had spoken often of her own education in art, which began as a 12-year-old in New Milford, Conn., with noted landscape and graphic artist Edith Newton. Becky earned her master's degree in fine arts from the prestigious Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles, now California Institute of the Arts (Cal-Arts), and studied with such notables as California watercolorist Rex Brandt and ceramic artist Marguerite Wildenhain, who was associated with the avant-garde Bauhaus School in Weimar, Germany, and founded the Pond Farm artists' cooperative in Guerneville, Calif. Still, when Becky thought back to the lives of the artists, she returned to her roots. In her writings, she asked herself, "Who of my century comes closest to living the ideal life of an artist?" Her answer was "not Sargent, not Picasso, not Cezanne, tho' the last comes close. No, Miss Newton, for her persistence, lack of self doubt, lack of apathy." She described Newton as "practical and intelligent," adjectives that described Becky as well. An annotation in one of Becky's notebooks reads,

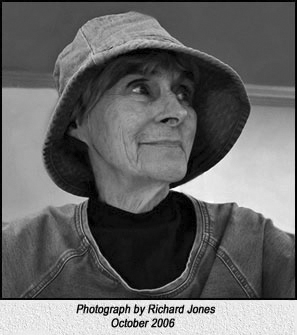

With a smaller house and yard, she expected to spend more time throwing pots and creating clay sculpture. "I'm trying to compress my duties so I can work more and read more," she said. She was entering her eighth decade and did not want to postpone her creativity. "I'm of that age," she said, but "I'm not thinking retirement, thank you very much." During that time, Becky taught watercolorist Don O'Neill of Riverside how to make pottery, and he inspired her to return to painting. They were married, and Becky moved back to Riverside in 2006. This was a temporary stop on her way to live among artists in a Laguna Hills community. Having returned whole-heartedly to drawing and watercolor, she did not plan to take her kiln. Becky looked forward to living and working among artists: "Joy, oh bliss," as she would say: Good things were coming her way. Donna Kennedy Riverside, California October 2006 |